THINGS I LOST IN THE DESERT

🏜🌵🐪

Alice Adams October 2022

Before:

🧵

there’s no strict definition of an ultramarathon – really anything longer than a marathon (26.2 miles/42.2km) counts

these distances feel long for most of us

in a couple of hours i leave for amman to run 250km in 5 days across the wadi rum desert

it’s not as impressive as it sounds. most people won’t run the whole thing – we’ll walk parts of it and stop for rests

it will be hard tho

i give myself around a 50% chance of finishing

i’m nothing special as a runner, pretty middle of the pack

the main price of admission is the time and willingness to train reasonably hard for 4-5 months

for me it’s the same as writing – beyond all the veneer of rational justification, there is some visceral urge that makes me do it even when i simultaneously just.want.an.easy.life

i started walking and running longish distances in the wake of profound loss

the body knows what it needs to do even as it tries to turn to stone

running is a way to inhabit my body as an animal

running is a prayer

running is integration

running is healing

running takes me out into the desert

(a deeply spiritual place)

with 130 other people who have the urge to run 250km across the desert

it selects for people i want to know

but there is of course a sense in which you’re very much on your own out there

a part of me fears it and a part of me craves it

running breaks me down and rebuilds me differently

it takes me to meet my limits – and they turn out to be nowhere near where i thought they were

(when you think you’re broken, that you can’t go any further, that you’re hitting the wall, that this is impossible, total bullshit, it hurts so bad you simply can’t go on….

…you’re at about 40% of your true limit

this is a thing worth knowing, really knowing, in your body as well as your mind)

it teaches me to appreciate comfort but not be its slave

it reminds me that whatever i do my body will eventually crumble and die

so i might as well have some fun in it in the meantime

you can learn to switch off the pain, or at least distance yourself from it

step back and say, ah, there you are old friend, you are right there and i’ll just be over here

and this generalises outwards to life

‘this is what you came for’

‘faster, it’s only pain’

the race is long and the end, only with yourself

~

tl;dr i’ve made some questionable decisions in my life and this may be one of them 😂 encouragement, thoughts, prayers and good vibes all welcome, especially around the middle of next week ✨

After:

The good news: I did a desert ultramarathon.

The bad news: I completed only one 45km desert ultramarathon, when I was supposed to do 250km over 5 days and failed.

I say failed; I don’t feel particularly fail-y, more a bit shit-happens-y.

But I did DNF (Did Not Finish) the race.

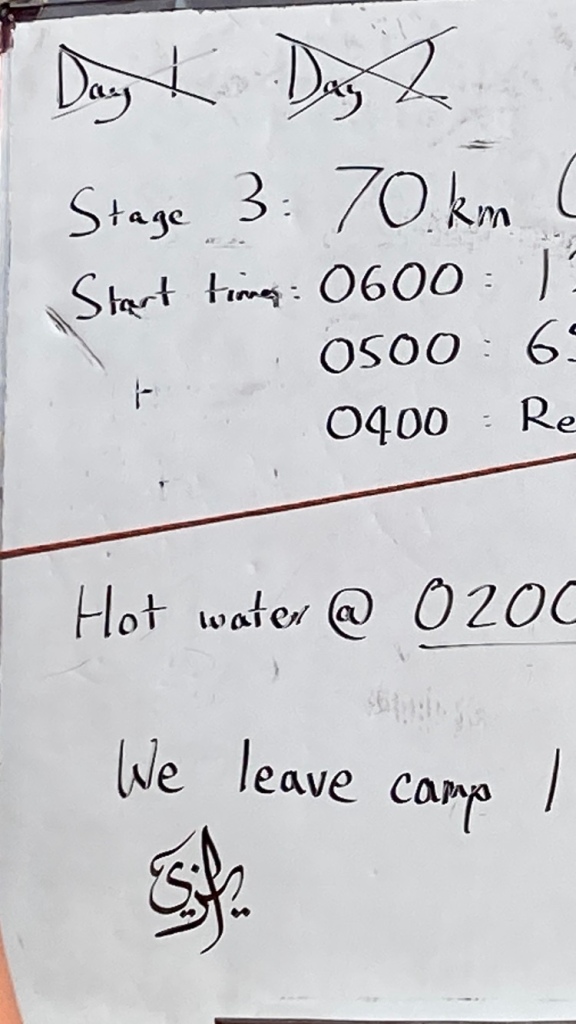

It’s 2am on day 3 and I’m lying in a sleeping bag in an open-fronted bedouin tent I’ve shared with 15 other people the last few nights.

‘If it only would be 50km instead of 70km today I wouldn’t be scared at all,’ the Finnish girl a few mats over is saying.

‘Do your best,’ Sheila tells her. ‘You’ll be fine.’

Sheila is Persian-Swedish and the same age and size as me, but unlike me she has already done two multi-day 250km+ ultras this year, one in the Peruvian jungle and one in the Arctic, and come first female in both.

We palled up at the airport and she graciously didn’t ditch me when it became apparent that one of us is an elite athlete and one of us very much isn’t. ‘I did Edinburgh marathon a few years ago but I don’t like those short distances,’ she tells me in complete seriousness, while I try and fail to keep a straight face.

‘It’s going to be a walking day today,’ our tent-mate Dave, who runs a 2:38 marathon, tells the Finnish girl.

In actual fact I have my doubts that anyone who tries to walk the long day is going to make it. I discovered a few years ago that walking long distances (say, 35km plus) is harder than running them.

The right amount of a 50km day for me personally to run at the start is 30km, pausing for water refills. After that walking is fine, but much less and it’s just too far and too long.

If you did 70km at a constant pace of 5km an hour you’d be out there for 14 hours – but in reality it will take much longer. You have to stop: to eat, to apply sunscreen, to fill your water bottles, to rest, to go to the loo, contend with heat and sand, and you get slower as the day goes on. And then you need enough time to sleep to be up at 5am to do it again the next day.

~

In the run up to the race I worried about all the wrong things.

I was expecting to meet myself out in the desert and I did. It turns out I am… more cheerful, more flexible and much better at sleeping in weird situations than I realised.

I generally consider myself a fairly rubbish sleeper, and feel like garbage if I don’t get at least six solid hours, which happens quite a lot. Hilariously, this week I seem to have been sleeping better than anyone else in camp. Everyone rolls out of bed groaning about having had two hours sleep and all the snoring, whereas earplugs, eye mask and nytol have done the job perfectly for me and I’m disgustingly chipper.

I expected to struggle with the lack of privacy but ultrarunners largely don’t care about bodily modesty or social graces, so they’re low effort to be around and anyone who wants to be left alone can just pull their sleeping bag up over their head. The whole thing has felt relaxed and fun, though possibly this is just the blissful ignorance of the inexperienced.

‘Ugh, I’m anxious. I can’t get my heart rate down,’ Sheila tells me as I stand yawning and stretching on the Day One start line, feeling pretty chilled and not at all worried about the thing I really should have been worried about: sand.

Man, sand is hideous stuff. It slows you down like you would not believe. It is simply unrunnable if you’re not some kind of super athlete like Salameh Al Aqrah (who wins this race every year, runs a 2h20 marathon and oh, is 53 years old.)

Day One went smoothly for me. It was 45km in 105 degree heat, significantly hotter than expected, but I managed my electrolytes and fuelling no problem, and never felt tired or nauseous. Everyone I spoke to was struggling to keep their heart rate at a sensible level in the heat but I never felt worried (except when we came across a disoriented German runner with what looked like heatstroke in a long stretch of open sand, but she was quickly rescued and recovered, though her race was over.)

That night in camp, rumours abound: there is 30km of unrunnable sand tomorrow; no, there is 20km of sand; the first 15 are on good fast runnable ground; the long day ends on a steep hill; 8 people have DNFed, no, 10 people have DNFed, Dave saw a scorpion by the rocks; there’s a guy out on the course with no electrolytes, he’s gonna die of sunstroke.

Day 2 I set out for the 50km feeling energetic and confident, and praying for the runnable terrain to last another 20km so I can get a jump on the day before the heat and sand slow me to an inevitable crawl. But 5km into the race my foot goes into a hole and I stumble pretty hard, though I recover my balance and don’t actually hit the ground.

From that point on I notice an acute pain on every foot strike low down on my left shin. I wait for it to get better. A bit of pain is just a part of running. You have one pain here, fifteen minutes later you have a different pain somewhere else. Whatever. But this pain stays and worsens for the next 7 or 8km until I have to admit to M, the friend I came with, that something is up and I need to slow down.

A few kilometres later I limp into the next checkpoint and consult the medic. ‘Can’t be sure without an MRI but if it were me I’d stop now,’ is the advice. The second opinion is the same.

I sit mulling it over. M is jittering around nearby, anxious to get back in the race. I’m never going to keep up with him like this. I’ve been round this loop before a few years ago, with a stress injury on my other shin which I made worse by running on it and then had to stop running for ages to let it heal. If you keep going on stress injuries they can turn into stress fractures, no one’s idea of a good time. Running is essential self care for me and long periods without it don’t leave me in a good place. Got a problem? Running™ will fix it, 99 times out of a hundred.

I imagine being back at the Fortius clinic with Dr Rees waggling his eyebrows at me admonishingly as he tells me I mustn’t run for months, and that I could have avoided this if only I hadn’t run on an injury. Even if I make the next checkpoint, I’m already falling behind and I have over 30km of a 50km day left and have already run on an injury for over half an hour. And even if I ignore the pain, which I’m totally happy to do if I’m confident I’m not properly injuring myself, it’ll be another 70km tomorrow. The finish line on Day Five is 185km away. I’m not going to make it. My race is over.

The rest of the day is spent hopping aid stations with an accumulating crowd of casualties waiting for trucks to take us to camp. I find Sheila at the next checkpoint. She was expecting to make the podium in this race but she’s torn a quad.

‘It’s like the bloody Somme at the next checkpoint,’ I hear someone mutter as I feed my remaining Tailwind to the guy who literally had no electrolytes and had signed up for the race 8 weeks before, and has quite remarkably failed to die of heatstroke.

Later we acquire Lewis, who’s simply lost his mojo. ‘I just can’t be bothered. I can’t explain it. I’ve done loads of marathons and ultras. I completed the Marathon des Sables. I’m just not in the right headspace.’

~

Back at camp, everyone is sympathetic to the twelve or thirteen of us who’ve DNFed that day. I try to work out how I feel. I didn’t train the way people like Sheila train, but I put in a fair bit of effort and spent a lot of money to be here.

I’m disappointed it’s over in such a stupid way, a way I never imagined. I wasn’t hellbent on reaching the finish line at all costs, because I know far, far better people than me who’ve DNFed races like this, but I can’t say I hadn’t imagined what it would feel like to cross the finish line on the final day, a dream that now dissolves into the bright desert air.

But worse things happen at sea. I can’t pretend this is a catastrophe. I’m still feeling inexplicably cheerful, as I have throughout. I’m aware there is something rather indulgent about this whole thing. We put ourselves through extreme stuff not to further the goals of humanity but just to feel things. Is this reasonable? Could our time and money and energy be better spent, in more altruistic ways?

We get to do this because we are rich, blessed with being born into the best time and place and circumstances in history. Deprivation gives us things we need because we get to go back to luxury afterwards. Experiencing anything for a short period is an entirely different thing to experiencing it for a long period. (This is why parenting is impossible to explain to anyone before they do it – its most salient property is its sheer relentlessness.)

I think the key is to recognise this for what it is: play. Play is a wonderful, indispensable part of living and growing but I don’t see this or any other sport as particularly noble pursuits – they have extreme highs and lows, so they feel high stakes, but they’re not, not really.

~

When M makes it back to camp, he tries to make soothing noises but I’m thinking about logistics, and tired, he manages to fumble it and say, ‘If it were me I’d want to get back to Amman as soon as possible because I’d feel like I’d let myself down.’

I can’t stop laughing. I don’t feel like I’ve let myself down. He apologises and wanders off happily inviting people to my place for dinner when they get back because he lives near me and his chairs are broken. I wonder if he’s quite alright after 95km in two days in the desert sun.

~

Things I Lost in the Desert:

- the race

- an intact shin

- bodily modesty

- the need for control

- my view of my own personality as something fairly fixed rather than super adaptable to circumstances

Things I Found in the Desert:

- a bunch of excellent new friends

- an exceptionally nice pebble, white and bulbous

- a few bits of myself that I’d forgotten existed

I think what it boils down to is this: we have different modes, and many of them we access so infrequently we forget we even have them. I have a mode in which I am viscerally in the moment and don’t think much, don’t intellectualise, don’t need much sleep or privacy, and it felt like a sliver of grace to reencounter it after a long time away.

I’m not going trad and fetishising a simpler life here; the longer I live, the more I come to think that maturity is knowing that everything’s a trade-off and that not realising/admitting this is the most widespread form of bad thinking or dishonesty.

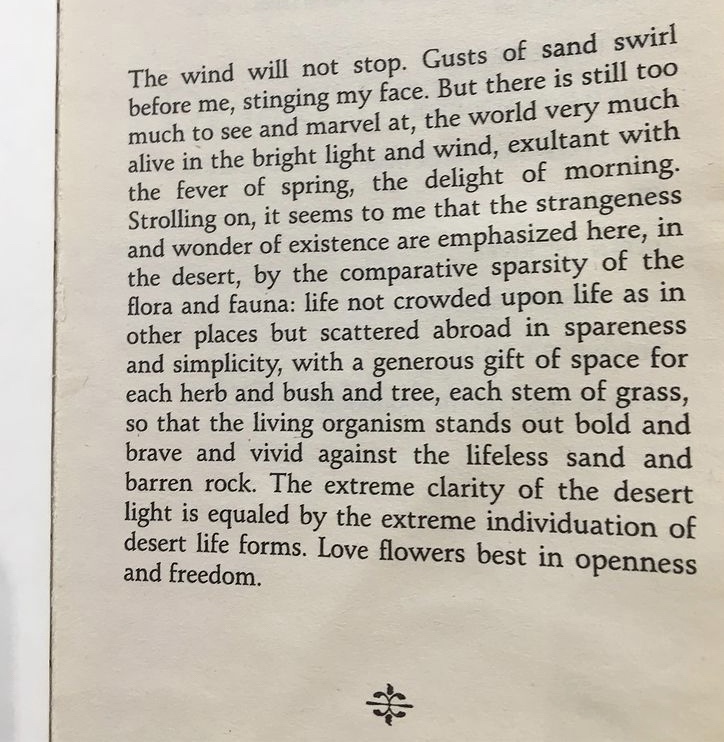

But my ascetic streak yearns for regular doses of the simplicity and pared back life and mind and experience I got in Wadi Rum. Paradoxically, as my life and attention shrink down to the basics, a vast, rich landscape opens up for me. It sits quietly in the background at all other times, its beauty and subtlety unnoticed and drowned out by noise. Out in the desert, it sharpens into focus, a symphony that has been playing all along but which I somehow failed to hear.

~

M wanders back and we sit in the fading light eating our disgusting expedition food out of a bag. He ran a lot of the day alone and had time to think, he tells me. So much of what we get bogged down in back home is insignificant. We tell ourselves stories and believe in them, and every so often we need the headspace to reconsider and make sure we’re telling ourselves the right stories, because you can live a whole life like that if you’re not careful.

And that’s when I understand what I’ve really lost today, the thing that slipped from my grasp out in the Wadi Rum: the loneliness of the long distance runner, the day I’d planned to run across the desert entirely on my own and reflect on my life and take a few decisions and perform an exorcism or two.

Monday was stunning – endless miles of desert, vast and empty, but I spent pretty much the entire day with and chatting to M and other runners. It was a happy day, morale was high, but it was very social – even the evening’s stargazing was done lying out on a rock with M and Dave.

That headspace and effortless reflection and integration out in nature – they’re the best thing about running. In that sense, I didn’t get what I came for. I got a lot of kit, and an unprecedented experience, but there was something I keenly wanted that I didn’t stay in the race long enough to get. I needed it to be longer and quieter and push me closer to my limits to get the distance and clarity and sense of closeness and oneness to the universe that I came for, that for now stays just out of reach of my seeking fingers.

I go and lie on my mat looking out at the desert and thinking about the journey home.

‘Don’t worry,’ say M and Dave and Sheila and Lewis. ‘There’s this great race we can sign up to for next year…’