Why Does Anyone Write?

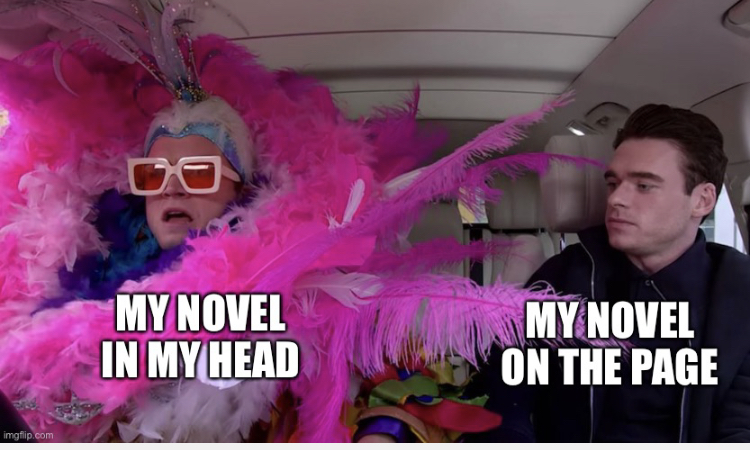

Writing a Novel can be a Painful and Bloody Process

All writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery. Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.

–George Orwell, “Why I Write,” 1946

Writing a novel is a painful and bloody process that takes up all your free time, haunts you in the darkest hours of night and generally culminates in a lot of weeping over an ever-growing pile of rejection letters. Every novelist will have to go through this at least once and in some cases many times before they are published, and since publication itself brings no guarantee of riches or plaudits, it’s not unreasonable to ask what sort of a person would subject himself to such a thing.

My own initial answer was similar to Orwell’s: a person sufficiently plagued by the urge to do it that they have no choice. I thought about giving up a million times before I completed my novel. I wanted to give up, to wrest back my life from the demon, but each time I tried I came up against the unavoidable conclusion that, for me, the only thing worse than a lifetime of slaving away in unrewarded obscurity (at that point the most likely outcome) would be a life without writing in it.

I didn’t set out to be a writer. As a child, being a novelist seemed like the most exalted possible career but it was like wanting to be a movie star, a wildly unrealistic dream. I remember the first time I found myself utterly immersed in telling a story, a dystopian sci-fi piece I wrote for a school assignment, in which humans left their environmentally-degraded planet in search of a new home aboard vast intergalactic spaceships called Arks. I was moved by the plight of my characters, awed by the immensity of the universe I had conjured into being, and heartbroken by the tragedy and sacrifice that lay at the heart of their mission. The fact that it was buttock-clenchingly sentimental tripe did not change the fact that writing it gave me flow, that elusive experience of total absorption in a mental activity, completely removed from my other worries and preoccupations. And finishing it gave me all the satisfaction of creation: here was a story that I had brought into the world, a tiny yet complete work of “art” which would never have existed had I not written it.

Anyway, after that I left school and real life took over. I had a youth to misspend, and then after that came jobs and rent to pay. For a short while I indulged in the fantasy of becoming a librarian but instead ended up working as an analyst in banking, where there were fewer books but more money. The work was interesting but it was also demanding, and crowded out room for other things in my life.

So that was it for ten years; in the decade from leaving school, my literary output was zero. But the itch was still there in the background, the urge to put words on paper, to construct stories around the things I cared about, to seek meaning through narrative. Eventually I started tinkering again, slowly and without any particular goal at first, then more seriously as I became immersed and started spending all my free time on it. It built from a niggle to a consuming furnace that burned through all my free time and mental energy. But what it that was consuming me? What was I writing for?

I once read another writer, I forget whom, saying that their writing was a sort of wolf call to their tribe, and I think there’s some truth in that; I write for my tribe, an imaginary group of readers who are a bit like me on the inside. They’ve quite often screwed things up in their lives, and they’re not always shiny and happy, because even the most average of lives contains great battles—growing up, finding meaning, living with loss, addiction, disability, infertility—but they’re trying to fight those battles with courage and humor.

Every so often a row flares up about whether literature has a responsibility to be redemptive. Responsibility is I think too strong a word; you can only write whatever you are moved to write. But I do think that nihilistic writing, or work that elevates misery, has nothing of value to add to the sum of human endeavor. It’s the work of a lifetime to keep your face turned towards the light, and I’d rather help than hinder people to do that. Almost everyone over the age of thirty surely knows what it is to look out into an apparently uncaring universe and feel despair, and as A.S. Byatt said in a Paris Review interview, tragedy is for the young, who haven’t experienced yet it for real; only they can afford it. So I’m in the “yes” camp: I want people to come away from my writing feeling hope, not that life will be easy and free of suffering but that as well as the inevitable suffering, life can also contain much hope and joy.

Returning, then, to Orwell:

For all one knows the demon [which drives the writer] is simply the same instinct that makes a baby squall for attention. And yet it is also true that one can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one’s own personality. Good prose is like a windowpane.

As with life, there is a great mystery at the heart of writing. My father has been known to claim that when he plays his best chess he can hear angels sing; I have been known to scoff at such hyperbole, but at its best, which is maybe a fraction of a single percent of the time I devote to writing, I confess to feeling more conduit than creator, as though I’m not doing the work myself but am merely the channel through which it arrives in the world.

So, with a respectful nod to Orwell, here are a few of the many reasons I write:

– Because it takes me out of my own head, away from my troubles.

– Because it gives me a shot, however remote, at creating something sublime and transcendent.

– Because I burn with rage at the world, and it seems like a better outlet than gratuitous violence.

– Because I long to capture things that are ephemeral before they evaporate into nothingness: the quietly ecstatic feeling of being in a garden at dusk in summer, the mossy scent of a lover’s jumper.

– Because putting something into words forces me to articulate my thoughts and shape them into a narrative, and that gives meaning to my life.

– Because purging myself on a keyboard is compulsive and addictive; I sit down to bang out a few hundred words and look up hours later to find it’s dark outside and I am damp with perspiration, limp in my chair but full of a queer satisfaction, emptied and stilled and sated.

The last reason is perhaps the most important: I write because books have opened up my world and saved my life over and over again, and that’s something I want to be a part of. What a wretched thing it is to be human, self-aware and yet lacking the answers to almost all the important questions: how should I live my life, is there a God, what is the Grand Unifying Theory for the universe, what happens when we die? And of course, no matter how comfortable a perch we manage to bag ourselves, we are always a mere tug of the veil away from disaster, a split second in which we don’t look before stepping into the road, a phone call away from learning that we will never see a loved one again. What darkness.

And yet into this darkness come tiny slivers and shards of light, barely more than a glow it often seems, and yet somehow they help you to see the path ahead. For me those glimmers have often come from books.

When I wanted to know how to see clearly and speak honestly, Diana Athill was there to show me. When I wanted to see the fireworks produced when cynicism and idealism collide, in strolled Martin Amis, cigarette dangling from lip. When I needed courage, Andrew Solomon pulled me to my feet. When I wanted to exult in the beauty of nature and solitude, Sara Maitland stood beside me. When I could do nothing but laugh at the absurdity of the whole damn shooting match, Jonathan Coe and David Nobbs did not forsake me. And when I grieved, C.S. Lewis reached out across the decades and said, Here, take my hand. You are not alone.

So that’s a great debt that I owe, and in many ways the reason I write is this: to reach out a hand and pull the next one up.

© Alice Adams